Thad and I decided to roll and smoke one last joint on the library lawn before going in. I don’t know why we thought that was a good idea; probably because we were stoned.

We hadn’t quite finished smoking the doobie when we found ourselves surrounded by Hood River’s finest. They patted us down and found about an eighth of an ounce of marijuana in a baggie in Thad’s pocket. Oregon had just voted to decriminalize possession of less than an ounce, but the new law hadn’t gone into effect yet. We were written up for a class C felony. Thad was closer to his eighteenth birthday than I was so he was remanded to adult court and I went into the juvenile system. My record would be expunged, which was good, but my sentence was pretty open ended which concerned me.

I think Thad got a fine and probation. I had to see a psychiatrist about my drug problem (he was a doper and had rolling papers on the mantel in his office) and I had to go to twice weekly meetings with my juvenile officer for as long as he thought my attitude warranted his attention. He was a bit of a dick, threatening to have me placed in a detention center and insisting I kneel with him and pray. I went to a couple of meetings with him. I showed up for a few more appointments which he blew off. I wrote him a letter stating that I had to walk downtown to get to these meetings and if he wasn’t going to be there I didn’t see why I should go to the trouble. I didn’t go to any more meetings and did not hear anything more about it.

A repercussion of getting arrested was my parents got together with all my friends’ parents every Thursday evening to discuss whose child led whose child down the evil path of drugs. At first these were heavy, dark evenings. I was forbidden to leave the house, forbidden to phone my friends. But we came to the realization that none of us were supervised Thursday nights. It was the perfect time to sneak out and get high together!

Thad hit upon the idea of making a tipi and moving out. We raided our garages, basements and attics for canvas tarps. Between us, we came up with enough material to make a twelve foot tipi (measured from the doorway to the back at floor level). The canvas was war-surplus stuff, some of it already thirty years old, in various shades of olive drab. We bought some Speedi -Awls and set to stitching it together on Thursday evenings in the covered basketball court at Westside School.

We got a book about tipis from the library and copied the pattern from a pamphlet Thad found at the local head shop. Angus brought his stereo which we plugged into an outlet at the school so we could listen to records while we worked. We got high, perhaps a little more careful not to be observed than we had been prior to getting busted.

Woods surrounded Thad’s house, which provided the tipi poles. We cut and peeled them, smoothing them with a hand planer and rasp and set them up in his back yard to cure, turning them daily so they wouldn’t warp.

We worked on the tipi with all the zeal and manic glee of prisoners tunneling their way to freedom. Over the course of several weeks we had the cover sewn and a serviceable set of poles prepared. Our tipi was completed. And so we relieved our parents of the burden of our continued delinquency by moving up in the woods.

Four of us moved into the tipi in April, 1974: Thad, Angus, Jeff and myself. We loaded the tipi and our supplies into Thad’s Willys and drove up Post Canyon. We found a suitable campsite where the power lines cross the road, just north of the stream.

We splashed across the creek and then turned left, making a trail up the creek about twenty yards to a clearing. It took multiple trips to haul in the poles and cover and all of our gear.

The tipi was small, just twelve feet from the door to the back. Constructed of faded green war surplus tarps, barely visible from the road, it blended in with the surrounding maples and cottonwoods. It was dark inside, the only light admitted through the door and the smokehole, which faced east. Thrift store carpets were spread on the ground for a floor. Extending from the floor to about four feet off the ground was an inner lining of blankets, which added some warmth and kept rain water from dripping on our beds.

We set up our bedrolls two to a side, heads towards the back, with room for our knapsacks next to our heads. The fire pit was just in front of the door, a little forward of the center of the tipi, with a raised mound of sod and a small wooden alter Thad had made just behind the fire. Our teapot resided on the mound of dirt and our stash, pipes, candles and matches were on the alter. Just to the left of the door we kept our fire bucket filled with water. We also kept a bamboo bong submerged in the bucket, to prevent the bamboo from drying and cracking. To the right of the door we had a small stack of firewood. The anchor rope stretched from the apex of the tipi poles to a peg driven into the ground just behind the alter. I had swiped a carved wooden mask from my folks house and suspended it just off the ground , tied to the anchor rope. We dubbed the mask “George”. My grandmother had brought it back from her travels as a souvenir. Inside it was inscribed with the words “Fiji Java”. George became our house god and we dubbed camp “Tipi Fiji Java”.

That spring was one of the nicest in memory. Day after day we sat around our outdoor cooking area in the warm sun listening to the birds sing, watching the cotton woods and maples leaf out. Our diet was mainly pancakes for breakfast and variations of rice stew for dinner. None of us really knew how to cook, but we were determined to learn! Lacking an oven, we were really missing baked goods and bread. Thad came up with an unleavened bread which was simply flour and water mixed to the consistency of putty rolled out into a patty about ¼” thick and fried in a mess kit. It was unappealing in texture, aroma and flavor. We tried mixing canned blueberries into the batter, which made it a delightful shade of purple and a little sweeter but it remained a very poor substitute for the bread we were craving.

Our pancakes were much more successful since we used Krusteaz mix and did not have to rely overly much on our own meager skills. We would tart them up with raisins or berries and sometimes mixed powdered Tang into the batter making a sweet orange cake.

After breakfast we would wash our dishes in the stream and sit around the campfire and smoke, or go hiking in the nearby woods, gathering firewood on our way back. Angus started making mobiles using bits of mirror and broken glass, He hung these randomly through the forest and around our camp. They would sparkle and chime delightfully with the slightest breeze.

In the evening we would move back into the tipi and pass the pipe around the fire. Pulling the bong out of the bucket by the door and firing it up was a nightly ritual. I can still remember the feel of the cool, wet cylinder of bamboo in my grip, the gentle gurgle and bubbling it made as I sucked the smoke through the water and into my lungs.

Although the road was little more than a muddy track, we were not far from town and our buddies from high school would frequently visit, driving up after dinner (sometimes bringing beer!). It was not unusual to find a dozen boys crowded into the tipi, sitting around the fire in a circle, passing a pipe and drinking.

The fire lit the interior of the lodge with a bright, friendly glow. Sometimes flaring up to brightly illuminate the faces of my friends, sometimes dimming, flickering up and down the tipi poles. We would sit around the fire chatting amiably until we succumbed to sleep and intoxication. One by one we would slouch and recline, staring up at the spiral whorl of the poles at the apex, the glimmering firelight dancing along the slender shafts. The smoke would twist up into the night, to the stars winking above the smokehole.

Late at night, when our guests had left, the four of us rolled out our beds and stretched out to sleep. As we dozed off the scurry of little feet could be heard throughout the tipi. We had become infested with mice. They had paths and tunnels that criss-crossed the floor, just under the carpet. It was maddening to hear them scamper directly under our heads and to be unable to reach them. We would jump up and grab large sticks from the stack of firewood, beating the carpet in a futile effort to club the little fuckers to death. We never got a one. Angus even had his favorite mouse club, a gnarled shillelagh with a knot on the end he dubbed The Klong. He would leap from his bed, grab The Klong and flail madly at the carpet. He was more of a hazard to his messmates than to the impish rodents beneath our floor.

As it turns out we had a very effective mouse trap working for us but we didn’t know it. When we took down the tipi to move it later that year we dumped out the fire bucket. There must have been fifty mouse carcasses in the water in varying stages of decomposition. Apparently an open bucket of water is irresistible to a mouse. Attempting to drink from the bucket they would fall in and drown. The only time we had disturbed that bucket in months was to remove the bong to get stoned, drawing our smoke through that cooling water!

Thad dropped out of high school that year, but Jeff, Angus and I continued to attend with varying degrees of success. Angus graduated and went on to college the next fall. I think Jeff graduated too but ended up in the Army. My appearances at school grew less and less frequent. I hung on to the bitter end. When I appeared for class, I showed up reeking of sweat and wood smoke, feathers from my ancient WW2 surplus mummy bag stuck in my hair, foggy with the residual high of continuous intake of drugs. I did not graduate.

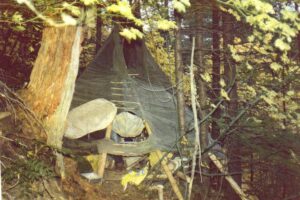

Thad and I moved the tipi up stream to where the canyon narrowed. There we built a platform out over the slope about halfway up the hill. excavating the uphill side and butting two long poles against the high side. We leveled them up and took the far ends of these logs out over the grade, lashing them to a tree about six feet off the ground forming a rude triangle. Thad’s father contributed some lumber slats he had left over from a house project; Thad and I cut these to fit and nailed them across the two logs to make the floor for our lodge. All but the Southern edge of the platform was elevated above the ground. We solved the problem of a firepit by cutting a square hole through the floor and staking large, flat rocks on edge to form a stone box from the ground to the surface of the wood . We filled this box with rocks and earth to make our hearth.

Thad and I moved the tipi up stream to where the canyon narrowed. There we built a platform out over the slope about halfway up the hill. excavating the uphill side and butting two long poles against the high side. We leveled them up and took the far ends of these logs out over the grade, lashing them to a tree about six feet off the ground forming a rude triangle. Thad’s father contributed some lumber slats he had left over from a house project; Thad and I cut these to fit and nailed them across the two logs to make the floor for our lodge. All but the Southern edge of the platform was elevated above the ground. We solved the problem of a firepit by cutting a square hole through the floor and staking large, flat rocks on edge to form a stone box from the ground to the surface of the wood . We filled this box with rocks and earth to make our hearth.

Some flaws in our plan became immediately apparent. Others showed up later. In the first category was the difficulty of getting a good set with the confined area afforded us by our platform. This, coupled with our inexperience, resulted in our tipi having a somewhat saggy and wrinkled appearance. We couldn’t get the poles spread out and set up properly nor did we peg the bottom down very well. With time we discovered the same lack of room limited our choices when adjusting the smoke flap poles, a major problem in the winter when the wind would back and blow from the East. The opaque military canvas cover admitted no light. When the fire died down, shadows gathered and the tipi took on the character of a cave. In addition to the campfire, illumination was provided by candles and kerosene lanterns.

Another problem we discovered after the rains came was that the south side of our tipi, the side which was up against the hill, caught the water and mud running down the hill and channeled the wet slurry into the tipi and Thad’s belongings. This progressively got worse and became quite an issue by the end of our stay. We also seriously underestimated the increased difficulty living on a hill added to hauling in water and food. Splitting and cutting firewood in camp could be problematic as well. If you slipped or dropped the piece you were attempting to cut it would quite often roll to the bottom of the hill.

People would also sometimes roll to the bottom of the hill. This could be considered a drawback but that was a matter of perspective. For the most part, we found it hugely amusing. Drunken, stoned guests, usually leaving in the dead of night, would step off the side of the trail leaving the tipi and find themselves twenty feet below where they’d started. Nobody got hurt but more than a couple of people were mighty surprised!

We wanted to reduce the number of casual visitors and avoid scrutiny by law enforcement (Thad and I were technically on probation. Although neither of us had to check in, getting busted again would have been a problem). To that end we deliberately obscured our trails and avoided a direct route into camp. To enter the draw one followed the irrigation ditch trail which traversed the opposite slope about halfway up. Leaving the ditch trail you descended to the bottom of the little valley and crossed the creek on a pair of vine maple roots that formed a bouncy and insecure natural bridge. From there a steep switch back brought you to a faint deer trail that ran across the side of the hill doubling back above the tipi. Just beyond our camp another switchback brought you downhill to our front door. We avoided cutting any trees or brush. Branches that obstructed the trail were bent back and lashed out of the way. If a trail became too worn and obvious, we would cut the lashing and put the brush back in place, moving the route over so it would not be so noticeable.

These precautions reduced the number of tourists, who showed up primarily to bum weed off us, but people still sought us out. During the day, perched at a vantage point on our hill, we could watch them attempting to find the trail in. If they were unwanted guests, we would keep quiet and eventually they would give up and leave. If we chose to visit, we would slip down and greet them, and bring them into camp along one of our more circuitous and difficult paths.

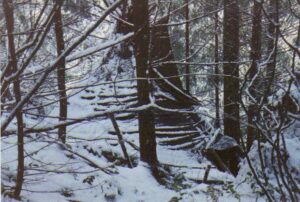

We wintered in that camp; it was, by turns,stunnigly beautiful and starkly miserable. When spring came, we moved camp one more time. We aired out our possessions and lashed them to the tipi poles, dragging them up over the ridge to our new site. After many trips we had all our gear in the new camp and raised the canvas into place. It was a pleasant campsite. There was a flat area outside the tipi where we had a fire and cooking area. We stacked our crates of food and some of our gear nearby. Post Canyon Creek ran behind the tipi and the door faced the hill, looking out on a waterfall and a small, seasonal creek coming down from the irrigation ditch on Riorden Hill. The clearing was surrounded by maples and cottonwoods, filtering the sunlight down on us through vibrant green leaves.

We wintered in that camp; it was, by turns,stunnigly beautiful and starkly miserable. When spring came, we moved camp one more time. We aired out our possessions and lashed them to the tipi poles, dragging them up over the ridge to our new site. After many trips we had all our gear in the new camp and raised the canvas into place. It was a pleasant campsite. There was a flat area outside the tipi where we had a fire and cooking area. We stacked our crates of food and some of our gear nearby. Post Canyon Creek ran behind the tipi and the door faced the hill, looking out on a waterfall and a small, seasonal creek coming down from the irrigation ditch on Riorden Hill. The clearing was surrounded by maples and cottonwoods, filtering the sunlight down on us through vibrant green leaves.

We didn’t put the liner up at this camp. The weather was fair for the most part, and the tipi seemed more open and roomy without it. There were a few hard rains during which we had to keep the fire stoked and stay back towards the edges to keep dry. The worst part was all the surface streams that would form and run through camp when it rained. On a rainy night when you ducked out of the tipi to take a leak you were certain to end up in running water up to your ankles as you stumbled around in the dark.

As the season wore on we spent more and more time in town, eventually getting jobs and moving back with our families. We left our tipi up Post Canyon and visited it often, sometimes alone, sometimes bringing friends. The tipi moved around for a bit, seeing use in tree planting camps and providing a spare bedroom at Cross Place in Eugene. The old canvas frayed and rotted. We finally retired it back up Post Canyon, to melt away in the forest that was it’s original home.

0 Comments